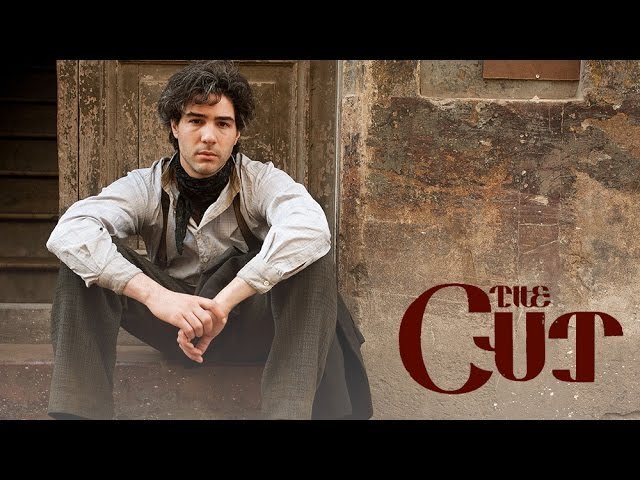

At this point, boxing films should no longer draw much attention since they hardly bring anything new to the table. Sean Ellis’ ‘The Cut’ addresses this challenge by portraying the physical and psychological aspects in addition to the stylized violence that occurs during the game. The movie attempts several things including the use of flashbacks but provides Orlando Bloom as an Irish fighter as the best redeeming quality of it all as he dominates the screen as the unnamed Irish fighter.

This man, who the media calls ‘the Boxer’, was, for some reason, never called by his name in the film, and appeared in only one boxing fight in ‘The Cut’. The figure on the trophy was really feeling himself at the start of the match, heading to a dominant victory in “The Cut,” when in an unforeseen, off-screen twist, something made him lose focus for a second and this cost him as his opponent sustained a gash.

This time, a decade later, the Boxer is running a run-down gym in Ireland with his wife Caitlin (Caitríona Balfe), and at one point, he even has to make himself throw up. His lifestyle may have altered, but his past haunts him. This is a subject that Bloom explores fully throughout the film, and deepens when his character gets a chance to return to the ring for a big Vegas prize fight on an interesting condition. The Boxer is told he will serve as a substitute for a fighter who died in camp because of dehydration, and as a result, the Boxer must lose 30 pounds in seven days. This is more than most people could expect to even hope to do in several months.

‘Oscar desirability’ cinematic transformations often go back to bodily transformations, there is a lot of that here, a lot of it present on screen, or even aggressive hair and makeup changes. There is no question that both of these help to explain how Bloom has changed over time. Indeed, his body bears the sculpting of his sustenance in his cauliflower ear and the cuts of his buzzed scalp hair and above the eyebrow. What however distinguishes Bloom’s act from the rest is the aspect of character. The Boxer is always restless and always defensive, has that look in his eyes trying to find something worth his time. He has a so-called hunger concealed in him, and his clenched face certainly exhibits traces of a rough childhood. The way he moves or even speaks is as if being in a labored state, and in order to push out words, he often has to snarl. It should be quite comical, pretty much how broad the impression of Connor McGregor would be like, were it not for the fact that Bloom moves in such a real way and as though he was being actively believed in what he earned.

At first when Caitlin becomes the lead trainer and the couple assembles their own crew, ‘The Cut’ becomes almost a self-referential boxing movie in that it merges two oppositional concepts, obsession and family, as if it were the same thing. In the sense of the ‘Rocky’ films, Adrian and Mickey are one and the same which makes Caitlin more active than a sports-movie wife on the sidelines, increasing the dramatic conflict inside her (and, in a more active way, the conflict within the sport). The complexities go up tenfold when, after seeing the pounds piling up on the scales and having pushed his body to the limits, the Boxer takes on a new trainer, Boz (John Turturro), who is a self-centered diabolic figure who achieves results because, as he says, he has a love for nothing or no one but winning.

“The Cut” depicts a nightmare training montage where the viewer sees grueling workout after grueling workout interspersed with imagery of meager, tasteless food rations (enough to get by). This film is also a display of the quiet male eating disorder. The viewer then eventually turns to see more of Ellis who’s recalled boxers eating in two worlds suffering in black and white, “Troubles”. Attached for Elsie is an attempt to plump the boxer’s architecture of the brain where the patients test psychosis Bloom, possessed by her career, performs so well, that these really become unimportant, and thanks to her acting already dominate couples more boring than dull training shots.

We might call ‘the Boxer’s’ origin story as it may be the case, has sinister angles that make his angsts walling about so at every instance, however explaining them is forever. It is suggested that “The Cut” might have been a better story had it focused solely on the hellish suffering of its main character. This tragic dimension’s psychology can be already comprehended in poetry and images, instead of literal description that sadly goes in a package with a movie’s nasty and pulsating hip-hop soundtracks that interpret the visuals. Ellis, who is also the film’s cinematographer, even uses extremely subjective horror images in such a way that they contribute to the Boxer’s drive and physical brutality: The Cut is particularly devoid of any single in-ring appeal and the triumph of competition more than a boxing picture should be able to have entirely taken cut also. Which is sufficiently gloomy and does not require excessive shifting away.

The agony that the Boxer has to endure should explain why the film addresses the dark side of sport because there is no denying that Blooms as painful as they are to watch come across as enough. While at least one, probably more, better versions than the one offered in “The Cut” exist, what appears in the film is still quite disturbing to the point that it lets Bloom’s character assert convincingly for the first time in his career ‘not the struggle, but its impressive outcome’.

For More Movies Like The Cut Visit on 123movies